When I was a Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose State University

in 2007-8, I used to drive my rattletrap of a car back and forth between San

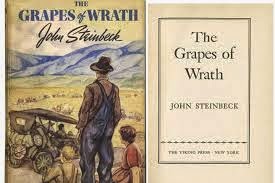

Jose and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood with The Grapes of Wrath

audiobook playing on my CD player.

I listened to the book twice in a row, all 21 hours and five minutes of it in 42 installments. As the story unfolded, I projected the action onto the land in front of me. While an amoral used-car salesman ripped off desperate “Okies” on their way to California, my own jalopy leaked oil on Highway 280. When Noah Joad disappeared, I imagined him lost in the foothills above Palo Alto. Twice in a row the lapsed preacher John Casy got his head bashed by thug cops while I crossed Church and 22nd Street in San Francisco’s Noe Valley neighborhood. “You don’t know what you’re doing,” Casy said to his tormentors as I found myself trapped behind a stalled-out streetcar. To this day, that upscale neighborhood feels like a tragic place; the taint never fades. Never mind that The Grapes of Wrath took place worlds away, in the San Joaquin Valley.

I listened to the book twice in a row, all 21 hours and five minutes of it in 42 installments. As the story unfolded, I projected the action onto the land in front of me. While an amoral used-car salesman ripped off desperate “Okies” on their way to California, my own jalopy leaked oil on Highway 280. When Noah Joad disappeared, I imagined him lost in the foothills above Palo Alto. Twice in a row the lapsed preacher John Casy got his head bashed by thug cops while I crossed Church and 22nd Street in San Francisco’s Noe Valley neighborhood. “You don’t know what you’re doing,” Casy said to his tormentors as I found myself trapped behind a stalled-out streetcar. To this day, that upscale neighborhood feels like a tragic place; the taint never fades. Never mind that The Grapes of Wrath took place worlds away, in the San Joaquin Valley.

To me, Steinbeck’s writing, at its best, is a lived

experience. It doesn’t matter when or where you read or hear it. No matter how

many times I revisit Grapes, I fool myself

into thinking the Joads will find what they need in California. John Casy will survive his confrontation with

the police. The heartache and disappointment feel fresh every time. So does the shock

of the book’s final image.

Steinbeck believed in slow writing. It takes forever to get to California. We

live through every mile with the Joads and their touring car, overstuffed with

belongings and people and always on the verge of breakdown.

To mark the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath, I got back in touch

with my former colleagues at SJSU, including Paul Douglass, an English and

American literature professor, and director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center

for Steinbeck Studies. “When I think of The Grapes of Wrath, I think of the

remarkable way in which it embodies the agony and transcendence of its era,” he

told me. “The dirt poor down low life of the transient population, uprooted and

outcast, and yet at the same time, the luminosity of the human spirit revealed

through the pressure of poverty and desperation.” I had a longer conversation

with Shillinglaw, a recent President’s Scholar Award honoree, and a longtime

professor of English and comparative literature at SJSU. She marked the 75th

anniversary with her new book, On Reading

the Grapes of Wrath (Penguin, $14.) Shillinglaw sat down with Catamaran to

talk about the origins of The Grapes of Wrath and the reason it continues to

enchant, infuriate and inspire generations of readers.

Read about our conversation in the latest issue of Catamaran, now available at a bookstore near you.